Candyce Carter is an alumna of Stanford’s Master of Liberal Arts program (she also received her B.A. in English and Psychology at Stanford). She is a 6th generation teacher and retired after forty years of teaching (mostly high school English). She lives with her husband in a fruit-packing plant converted into condos in beautiful downtown San José, CA. With her husband, she enjoys traveling, play- and movie-going, and Cardinal football

Fig. 1. Alexander Rider, “But I did not want to go…” from Torrey, Jesse. A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery, 42. Stanford Special Collections.

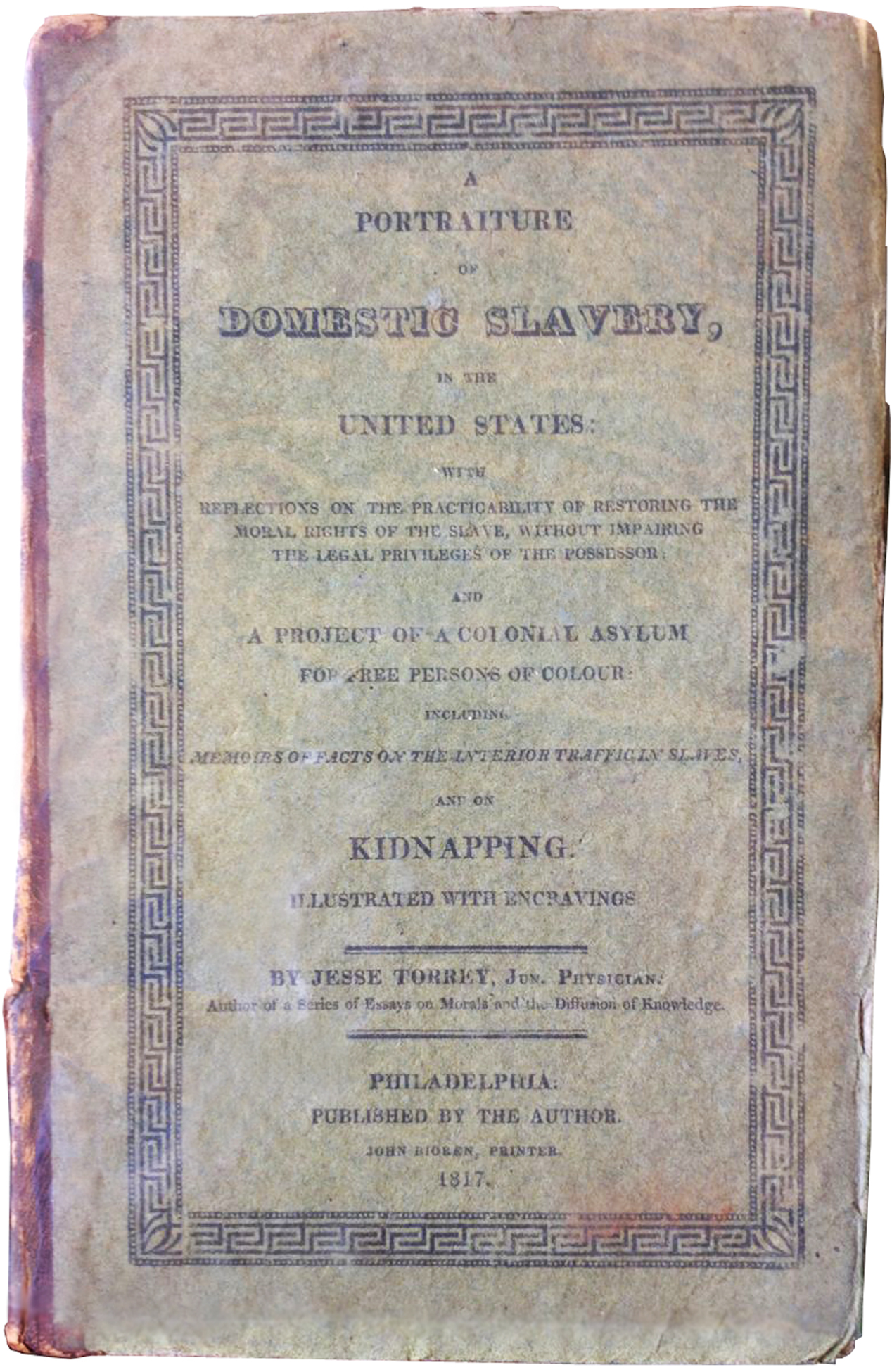

Fig. 2a. Frontispiece, A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery in the United States. Author’s photo. Stanford University Special Collections.

Figs. 2b and 2c. A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery in the United States, book cover and pages. Author’s photos. Stanford University Special Collections.

Fig. 3. Alexander Rider, “The author noting down the narratives…” from Jesse Torrey, A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery (46). Stanford Special Collections.

nonfiction

What Happened When Anna Jumped from the Window: The Domestic Slave Trade in Antebellum Washington, D.C.

Candyce Carter, Stanford University

The woman known as Anna awakened at daybreak in November 1815 and jumped from a third floor window of the Washington, D.C. tavern where she was being held. In the arresting engraving that depicts her desperate act, Anna’s facial features are shadowy. However, her dark, tightly curled hair and the contrast of her skin against the simple white cotton muslin dress make her racial identity unmistakable (Fig. 1). The anguished leap put Anna’s picture and story in one of the earliest anti-slavery writings of the new United States. Anna’s picture put a face on the inhumanity of the domestic slave trade, and her story indirectly launched court cases, started the American Colonization Society, inspired congressional speeches, caused her tavern-prison to burn to the ground, and put her jailer out of business.

An outline of the events that set Ann’s life in motion and put her on the window ledge that morning reveals scant details. Born into slavery in Maryland, Anna later married an enslaved man from a nearby plantation and had two daughters. At some point, Anna and her children were sold by her “old master” to her husband’s owner as payment for debts. Anna was “treated unkindly” in this new setting, and her new master also had debts. After sending Anna’s husband to work at the plantation’s outer perimeter, the planter sold Anna and her daughters to “men from Georgia,” who took them to Washington, D.C. to await further transportation.[1] It was in Washington D.C., while warehoused in the garret of George Miller’s tavern on F Street, that Anna jumped from the window. Miraculously, she survived, although she broke both arms and badly injured her back.

A few weeks before Anna’s leap from the window, Jesse Torrey, a Philadelphia doctor on a young man’s tour of Washington, D.C., experienced a ‘road-to-Damascus’ epiphany when he observed slave traders force-marching a sorrowful procession of enslaved men, women, and children past the Capitol building. Torrey recognized the irony of a parade of humans in chains in full view of the proud structures of a new republic founded on ideals of liberty and equality. The young doctor immediately canceled his Congressional visit and instead determined to create a “faithful copy of the impressions… which involuntarily pervaded my full heart and agitated my mind.”[2] The story of Anna’s jump from an upper story window of a “slave tavern” came to Torrey’s attention as it circulated through Washington’s rumor mill. Torrey rushed to investigate and discover what motivated Anna’s hopeless and “frantic act.” Perhaps Torrey knew instinctively that the story of one mother’s desperation fully captured slavery’s brutal reality in ways that reduced other discussions to mere abstractions. Anna’s is the first of several accounts of Torrey’s interviews with enslaved persons, slaveholders, slave traders, and kidnapped free African-Americans in A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery, a slim, 84-page leather-bound volume Torrey published within two years of Anna’s leap from the window (Figs. 2a, 2b, 2c).

When Torrey met with Anna, she was lucid but bedridden—and once again in the third-story garret of Miller’s Tavern. Miller had purchased her for the bargain price of $5, presumably enough to cover the cost of her care until she recovered.[3] Torrey’s interview with Anna does not reveal whether she was trying to escape when she jumped, or whether she intended to take her life. Nevertheless, the reason Anna “did not want to go” echoes through slave memoirs and literature even today: the brutality and deprivation of the domestic slave trade and the deliberate dissolution of enslaved families. Anna was one of nearly one million slaves forcibly separated from their families and sold “down the river” during the first six decades of the nineteenth century. The narrative that accompanies the illustration quoted Anna directly: “They brought me away with two of my children, and wouldn’t let me see my husband—they didn’t sell my husband, and I didn’t want to go. I was so confused and ’istracted that I didn’t know hardly what I was about…they have carried my children with ’em to Carolina.”[4] “Thus,” Torrey adds, “her family was dispersed from north to south…without the shadow of a hope of ever seeing or hearing from her children again.”[5]

Torrey’s sympathetic narration of Anna’s despair exposed the human toll of the domestic slave trade, but it was Alexander Rider’s engraving that firmly secured her place in history. The obvious anguish of the woman in the illustration made Anna an accidental avatar for the fledgling anti-slavery movement. The illustration is inexpert—almost childlike in its inaccuracies—yet its crudeness is precisely why it is so haunting. Undoubtedly following Torrey’s careful description, Rider included other buildings in the F Street neighborhood: the spindly trees, the cobbled streets, and the dim sky of a cold November morning. The streets are empty and lifeless, as though the entire world has turned its back on Anna’s plight. Anna’s figure—larger than any window of the closest building—appears to have come from nowhere, as though she has dropped from the sky. The caption informs viewers that she “jump’d out of the window,” yet Anna’s position is discordant and disconcerting, given the physics of human bodies in free-fall. Her arms hang to her side. Anna does not fling herself out into space, or embrace death with arms wide open. She does not tumble and her skirts do not fly. Instead, her legs draw up demurely, as though she sits in a chair with skirts arranged modestly around her ankles. Perhaps Rider did not understand the obvious physics of a falling human body. Perhaps he intended to convey Anna’s resignation and assumed she wanted to die because life as a female slave was physically burdensome and spiritually overwhelming.

Anna appeared again in the next illustration in the book, which revealed how she indirectly led Torrey to uncover another pernicious practice in Washington D.C.’s slave trade. During his meeting with Anna, Torrey discovered three more prisoners held in the same room in the tavern. The image of the conversation that followed showed Torrey interviewing these cellmates while Anna laid under the dormer (Fig. 3). One of the companions, a 21-year-old “mulatto” man, was “thoroughly secured in irons.” The other two people were a “widow woman with an infant at her breast” (unrelated to the man) who was “seized and dragged” out of bed in her home.[6] Torrey was outraged to learn that—unlike Anna, who was a “legal” slave—the man, woman, and child were all free-born Americans kidnapped from Delaware homes.[7] These events evidenced to Torrey that any person of color, regardless of status, free or slave, was vulnerable to the vagaries of the institution of slavery.

Anna’s story and that of her fellow prisoners formed the basis for some unusual alliances. The first of these connections was with “Star Spangled Banner” lyricist (and attorney) Francis Scott Key. With Key’s help, Torrey obtained a court injunction to forestall the enslavement of the man and the woman and her infant who were being held with Anna. The petition was successful, and all were eventually returned to their free status in Delaware.[8] This was not the first—or last—time that Key offered legal assistance to free or enslaved people of color. He appears frequently in the Digital Research for the Humanities website, “O Say Can You See?”: Early Washington Law and Family, an online research hub of “multigenerational black, white, and mixed family networks in early Washington, D.C.” Indeed, Key’s name appears in 117 cases (an unusually high number) under review, nearly always as the attorney for enslaved people petitioning for free status.[9] Anna was thus one of many such plaintiffs who used Key’s legal services.

Key’s advocacy is inconsistent, however, with his well-documented racist views and his status as a wealthy Marylander from a prominent slave-owning family. In an article for Smithsonian, “Where’s the Debate on Francis Scott Key’s Slave-Holding Legacy?”, Christopher Wilson, Director of the African American History Program and Experience at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, cites Key’s comment that African-Americans were “a distinct and inferior race of people.” Wilson also points out that Key was also vehemently opposed to the abolitionist cause and used his connections and courtroom access to censor abolitionist publications and speeches.[10] Key’s alliance with Torrey, the writer of the one of the earliest anti-slavery texts in the United States, and his legal efforts on behalf of enslaved people such as Anna, reflect the tortured paradoxes embedded in the “peculiar institution” of slavery.

Torrey gained another even more unlikely ally in John Randolph, a Virginia slave owner and congressional representative. Randolph realized that the image of a desperate slave woman jumping out of a building made a mockery of his earlier claims that slavery was a benevolent institution. Randolph was also painfully aware that European visitors to the United States sent home horrified reports about the omnipresence of enslaved people in the capital of the new republic. One such tourist, Irish poet Thomas Moore, whose poems of his American travels were published in England, wrote:

Even here beside the proud Potomac’s stream…

Who can, with patience for a moment see

The medley mass of pride and misery,

Of whips and charters, manacles and rights,

Of slaving blacks and democratic whites…

Congressman Randolph tried in vain to convince colleagues to honor Washington’s “federal” nature by banning the slave trade within the capital’s jurisdiction.[12] Randolph also joined Torrey as one of the earliest proponents of what became the American Colonization Society, which sought to found a colony in Africa for freed African-Americans. As historian Nicholas Wood explains in his biographical study of the legislator, Torrey’s book—and Anna’s act in particular—exposed the depravity of the slave trade in the capital city in ways that even a slavery apologist like Randolph could not ignore.[13]

Randolph’s congressional speech-making notwithstanding, the selling, trading, kidnapping, and forced movement of enslaved, or kidnapped, African-Americans continued to be big business in Washington, D.C. up until the Civil War. Part of the appeal of the capital was pure geography. Half of the 750,000 people in bondage in America in the early nineteenth century lived in the Potomac region. Located between Maryland and Virginia with easy access to seaports and rivers, Washington, D.C. was the ideal depot for warehousing slaves en route to plantations to the south and west.[14] Washington residents like the tavern owner George Miller profited from holding captive enslaved people who waited to be sold. These profiteers also served as brokers for traders, as intermediaries for owners looking for escapees, and as bankers for anyone who wanted to purchase slaves. Frederick Douglass spoke of his “sorrow” about the links between slavery and the nation’s capital in his “Lecture on Our National Capital”:

sandwiched between two of the oldest slave states, each of which was a nursery and a hot-bed of slavery; surrounded by a people accustomed to look upon the youthful members of a colored man’s family as a part of the annual crop for the market: pervaded by the manners, morals, politics, and religion peculiar to a slaveholding community, the inhabitants of the National Capital were, from first to last, frantically and fanatically sectional. It was southern in all its sympathies and national only in name.[15]

African-American residents of Washington, D.C.—enslaved as well as free—also formed the backbone of the work force that built the city as it emerged from the banks of the Potomac in the early nineteenth century. Plantation owners of nearby properties were compensated for “Negro hire,” and enslaved workers of color—who outnumbered their manumitted counterparts five to one—were sent to construct the new republic’s iconic federal structures.[16] Planters whose enslaved workers labored in Washington, D.C. received monthly compensation of five dollars per laborer. This arrangement was a bonanza for slave-holders, who profited from their slaves’ labor without having to be concerned about housing and feeding them. Planters were expected to provide only a blanket for each slave they hired out. Records rarely revealed the names of these enslaved laborers, and it was not until the year 2000 that federal legislation authorized any systematic effort to document the role of enslaved workers in the construction of the nation’s capital.[17]

Nevertheless, Anna and her two daughters were not in Miller’s Tavern as part of an enslaved construction crew. Rather, they were sold as part of what historian Edward Ball called “Slavery’s Trail of Tears,” the forced movement of enslaved people from the Upper South (states including Virginia, Maryland, and Kentucky) to the “Old Southwest” or Deep South (such as Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama). The domestic slave trade sprang to life when the importation of a captured and enslaved African labor was halted in 1808. Washington, D.C.—with its easy access to transportation by water and land and its geographic location near large slave-holding states—became a hub for the involuntary movement of enslaved people to an ever-expanding agricultural empire. For more than six decades, approximately one million enslaved people traveled overland in coffles, or by water chained and manacled in riverboats and ocean-going cargo ships. Their numbers exceeded those of the native tribes in the infamous “Indian Removal” campaigns of the 1830s. Likewise, enslaved people taken from their families and familiar surroundings outnumbered the free and predominantly white migrants who volunteered to join wagon trains headed west. Ball, himself a descendant of a slave-owning family, reported that “this movement lasted longer and grabbed up more people” than any other human march—voluntary or involuntary—in North America before 1900.[18]

Ironically, the engraving of her leap from the tavern window depicts Anna wearing the source of her own misery—cotton—on her back. Light, washable, and easily dyed, the arrival of cotton fabrics from India and the Americas triggered the rage for “Grecian robes” for Enlightenment-era fashionistas from Paris to New York. Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin, and the availability of new lands in the south and west that followed the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, converged to meet consumer demand. Planters traded their increasingly unprofitable tobacco fields—and their slave labor—for cotton plantations in other regions. And because of its durable longer staple, American cotton was simply better, preferred by manufacturers on both sides of the Atlantic over the relatively brittle cotton from the Indian subcontinent. As manufacturers in England and New England competed to develop cheaper methods for the production and dying of cotton for mass consumption, cotton fashions expanded swiftly down the social ladder, as Anna’s simple muslin frock confirmed.

King Cotton turned the United States into a key player in the global economic marketplace. Enslaved laborers, subject to physical and mental distress for more than three hundred years, played an essential role in the economic development brought by cotton cultivation. The cotton gin, invented to expedite de-seeding of the notoriously labor-intensive Upland cotton, did not reduce the demand for enslaved workers. On the contrary, Upland cotton could be raised in a wider variety of conditions, so the gin expanded cotton cultivation into new regions. Planters, eager to expand their holdings further south and west, showed little concern about maintaining the family connections among their enslaved workers. Anna’s family was only one casualty among thousands.

Thomas Jefferson referenced this trend in 1820 when he wrote optimistically to the Marquis de Lafayette of the expansion of slavery into new areas: “All know that permitting the slaves of the South to spread into the West will not add one being to that unfortunate condition, that it will increase the happiness of those existing, and by spreading them over a larger surface, will dilute the evil everywhere, and facilitate the means of finally getting rid of it.”[19] The familial and community connections that would be forever torn apart by this “spreading” apparently never crossed Jefferson’s mind—or the minds of his slave-holding colleagues.

The ownership of slaves guaranteed the labor needed to work the various plantations and crops that allowed property owners to expand and diversify their holdings. In addition, enslaved workers served as collateral to obtain credit or cash. Slaves were also sold off to pay debts. Anna’s narrative reflected this practice, as both her owners settled their debts through the sale of Anna and her children. In Empire of Cotton, Sven Beckert cites historian Bonnie Martin’s research, which shows that slave-holdings, the number of slaves owned by any one person, accounted for at least partial collateral for eighty-eight percent of all loans in Louisiana and eighty-two percent in South Carolina.[20] The domestic slave trade was lucrative for others as well, and profits lined the pockets of traders, brokers, auctioneers, and jailers alike. For example, in 1857, the city of Richmond, Virginia reported slave sales that amounted to four million dollars, the equivalent of $440 million in 2015. Slave trader James Franklin agreed to bring “a good lot” of enslaved people to a purchaser in Natchez, Mississippi. The coffle he marched from his base in Arlington, Virginia to Richmond was valued at $300,000 in today’s money.[21] With ready access to ports, rivers, and overland routes, Washington D.C. thrived as a result of the profitable trade in human lives.

The threat of separation from family members, or the dreaded prospect of sale into harsher conditions, loomed over the heads of slaves and provided slave-holders with a form of emotional and psychological control over their human property. Anna’s suffering was part of a larger landscape in which historian Walter Johnson estimated that fifty percent of domestic slave sales in the antebellum period divided a family.[22] Anna described her terror when she learned that she and her children could be sold to pay her profligate owner’s debts. In an 1836 interview with abolitionist writer E. A. Andrews, Anna recounted that she “fell upon her knees to her young master and begged him that she and her children might not be separated from her husband and their father.”[23] Her entreaties clearly fell on deaf ears, for within days, the traders came for her and her daughters.[24] Their market value was too high for Anna’s planter-owner to ignore.

The fear of being uprooted had a far-reaching socio-political impact. Historians speculate that the relatively low number of slave revolts in the United States—in comparison with other slave-holding regions such as Haiti and Brazil—was attributable to the risk of being sold and moved to another location. As Johnson explained in his work Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market, “under the chattel principle…every reliance on another, every child, friend, or lover…held within it the threat of its own dissolution. Slaveholders used that threat to govern their slaves.”[25] English-American geologist George Featherstonhaugh, who traveled widely throughout the southern states on a federal survey tour in the 1830s, made a similar observation. He remarked that “the danger of revolt diminishes…this infernal trade of slave-driving…is a greater curse than slavery itself, since it too often dissevers for ever those affecting natural ties…by tearing, without an instant’s notice, the husband from the wife and the children from their parents.”[26] Persistent anxiety about the possibility of separation from loved ones—as Anna suffered—or sold and relocated to harsher surroundings—as Anna’s children experienced—kept the enslaved human chattel on the knives’ edge of fear and suspicion.

Although King Cotton kept Washington, D.C.’s slave pens and taverns in operation until the signing and enactment of the Emancipation Proclamation, the stories of Anna and her jailer, George Miller, provided a more satisfying conclusion to an otherwise sorrowful narrative. Torrey’s book and the unsettling illustration of Anna’s jump from the garret window secured Anna’s place in neighborhood lore, and made the illiterate and then-disabled African-American woman a local legend. Washington, D.C. historian Wilhelmus Bryan described what happened when, two years after the publication of Torrey’s book, a fire engulfed the outbuildings of Miller’s Tavern. As the tavern burned, neighbors in local fire brigades arrived with buckets to douse the blaze. When they assembled, they talked about Anna and other involuntary tavern “guests.” Many, like post office clerk William Gardner, announced loudly that they would do nothing to help the “Slave Bastille.” They turned their attention to nearby properties and allowed the tavern to burn to the ground.[27]

Miller did not prosper after the fire that destroyed much of his operation. Articles in Washington D.C. newspapers from 1819 onward carried frequent notices of property seizures for payment of his debts and back taxes. By 1824, a front page National Intelligencer notice announced that a new owner had restored and re-named the tavern as Lafayette House, although it continued as a slave-holding site.[28] An article in the May 30, 1829 issue of the National Intelligencer identified Miller as one of three individuals indicted by the Grand Jury of Savannah for false imprisonment of Rowland Stephenson.[29] Stephenson was, interestingly, neither enslaved, nor an American. He was a slippery English banker on the lam whom Miller and a fellow slave trader William Williams abducted in hopes of receiving reward money for his return to angry investors. Miller and Williams both pled guilty and were fined and imprisoned.

An interview by E.A. Andrews in 1836 reveals more about Anna’s life after she jumped from the window. According to Andrews, Miller claimed Anna as his slave after her jump from the window. Although her husband “[continued] as a slave,” he was able to join her in Washington.[30] Anna and her husband had more children, two of whom were living at the time of her meeting with Andrews. In the meantime, perhaps because of Miller’s legal and financial troubles, Anna resided “at liberty” in Washington, D.C. Court documents and Andrews’s account show that in 1828, Miller and his son George Miller, Jr., attempted to claim Anna’s surviving children as slaves. Again, Francis Scott Key appeared as an attorney when Anna petitioned for manumission of both herself and her children. The court found in their favor, and Anna and her youngest children were freed.[31]

Anna did not know what she was starting when she jumped from the third-floor window of Miller’s Tavern on that cold November morning in 1815. Her story, whispered among the respectable white citizens of the new capital, challenged slavery’s defenders, like John Randolph, and galvanized a young Philadelphia doctor to expose, in print, the evils of the domestic slave trade. Anna’s white neighbors remembered and avenged her when they let George Miller’s tavern burn to the ground. From Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, to Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and Toni Morrison’s Beloved, both white and African-American authors draw on Anna’s story, and extend and develop the family separation trope as a common thread in American literature. Like her oversized silhouette on the tavern wall, Anna continues to cast a long shadow.

[1] Andrews, E. A. “Story of Old Anna and Her Children.” Slavery and the Domestic Slave-Trade in the United States. (Boston: Light and Stearns, 1836), 129. https://archive.org/stream/slaverydomestics01andr/slaverydomestics01andr_djvu.txt.

[2] Torrey, Jesse. A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery, in the United States: With Reflections on the Practicability of Restoring the Moral Rights of the Slave, without Impairing the Legal Privileges of the Possessor; and a Project of a Colonial Asylum for Free Persons of Colour: Including Memoirs of Facts on the Interior Traffic in Slaves, and on Kidnapping. (Philadelphia: Jesse Torrey; John Bioren, Printer, 1817), 40. Also online: https://archive.org/stream/portraitureofdom1817torr#page/32/mode/2up.

[3] Ibid, 43.

[4] Ibid, 46.

[5] Ibid, 47.

[6] Ibid, 48.

[7] Ibid, 42.

[8] Holland, Jesse J. Black Men Built the Capitol: Discovering African-American History in and Around Washington, D.C. (Guilford, CT.: Globe Pequot Press, 2007), 83.

[9] Thomas, William G. & Nash, Kacie, Center for Digital Research in the Humanities. Oh Say Can You See? Early Washington, D.C., Law and Family. “Francis Scott Key.” http://earlywashingtondc.org/people/per.000001.

[10] Wilson, Christopher. “Where’s the Debate about Francis Scott Key’s Slave-Holding Legacy?” Smithsonian.com (July 1, 2016). http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/wheres-debate-francis-scott-keys-slave-holding-legacy-180959550/?no-ist.

[11] Moore, Thomas, “To Lord Viscount Forbes, From the City of Washington,” 256-257. The Poetical Works of Thomas Moore (Edinburgh: William P. Nimmo, 1863), quoted in Lauret Savoy, Trace (Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2015), 168.

[12] U.S. Congress. House. “Committee Appointment: Inquire into the Existence of …traffick in Slaves, Carried on in, and through the District of Columbia.” Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States at the First Session of the Fourteenth Congress, in the Fortieth Year of the Independence of the United States. 1815. 424. www.hathitrust.org.

[13] Wood, Nicholas. “John Randolph of Roanoke and the Politics of Slavery in the Early Republic.” Virginia Historical Society, Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 120.2, (Summer 2012): 119, http://www.vahistorical.org/read-watch-listen/virginia-magazine-history-and-biography/.

[14] Holland, Jesse J. Black Men Built the Capitol, 3-4.

[15] Douglass, Frederick. “Lecture on Our National Capital,” n.p. (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1978) http://lcweb2.loc.gov/service/gdc/lhbcb/02756/02756.pdf. Quoted in Lauret Savoy, Trace, 167.

[16] Savoy, Lauret. Trace, 168.

[17] Holland, Black Men Built the Capitol, 3-4.

[18] Ball, Edward. “Slavery’s Trial of Tears.” Smithsonian 46, number 7 (Nov. 2015): 63.

[19] Mintz, S., & McNeil, S. “Thomas Jefferson: Letter to Lafayette on Slavery.” Digital History. http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook_print.cfm? smtid=3&psid=230.

[20] Martin, Bonnie. “Slavery’s Invisible Engine: Mortgaging Human Property,” Journal of Southern History 76, no. 4 (November 2010), 840-841, cited in Sven Beckert. Empire of Cotton: A Global History. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014), 114.

[21] Ball, Edward. “Slavery’s Trail of Tears,” 60-62.

[22] Johnson, Walter. River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom. (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013), 14.

[23] Andrews, E. A. Slavery and the Domestic Slave Trade in the United States, 130.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Johnson, Walter. Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999). 22-23.

[26] Featherstonhaugh, George. Excursion Through the Slave States. (London: John Murray, 1844). 124. https:books.google.com/books.

[27] Bryan, Wilhelmus B. “A Fire in an Old Time F Street Tavern and What It Revealed.” (Records of the Columbia Historical Society. 9, 1906: 198-215), 198-201. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/40066941. Also exchange of letters: Gardner, William. “To the Public.” City of Washington Gazette IV.449 (1819): 5. Miller, George. “To the Public.” City of Washington Gazette IV.458 (May 11, 1819): 3.

[28] Holland, Black Men Built the Capitol, 28. Also “Lafayette House.” Daily National Intelligencer XII.3669 (October 22, 1824): 1.

[29] “Grand Jury, Savannah.” Daily National Intelligencer. XVII.5095 (30 May, 1829): 3.

[30] Andrews, E. A. Slavery and the Domestic Slave-Trade in the United States, 132.

[31] Ibid. Also: William G. Thomas and Kaci Nash. “Ann Williams v. George Miller and George Miller Jr,” Oh Say Can You See? Early Washington, D.C., Law and Family. http://earlywashingtondc.org. Personal correspondence between Thomas and Nash and Author. 28-30 March 2015.

Copyright © 2017 by Association of Graduate Liberal Studies Programs