Lee Casson is a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University, enrolled in the Master of Liberal Arts program. He also holds a Doctorate in Education and a Master of Arts degree in English from the University of Tennessee.

Figure 1. The Turkish Bath, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, circa 1860.

Figure 2. The Large Pool of Bursa, Jean Léon Gérôme, 1885.

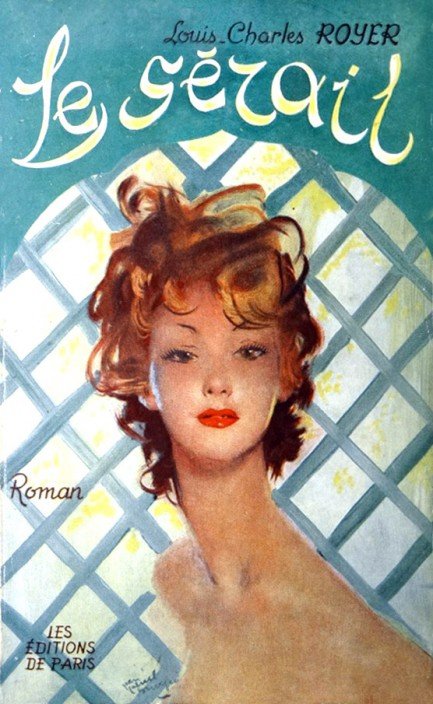

Figure 3.

Le Sérail, Louis Charles Royer,

early 1930s.

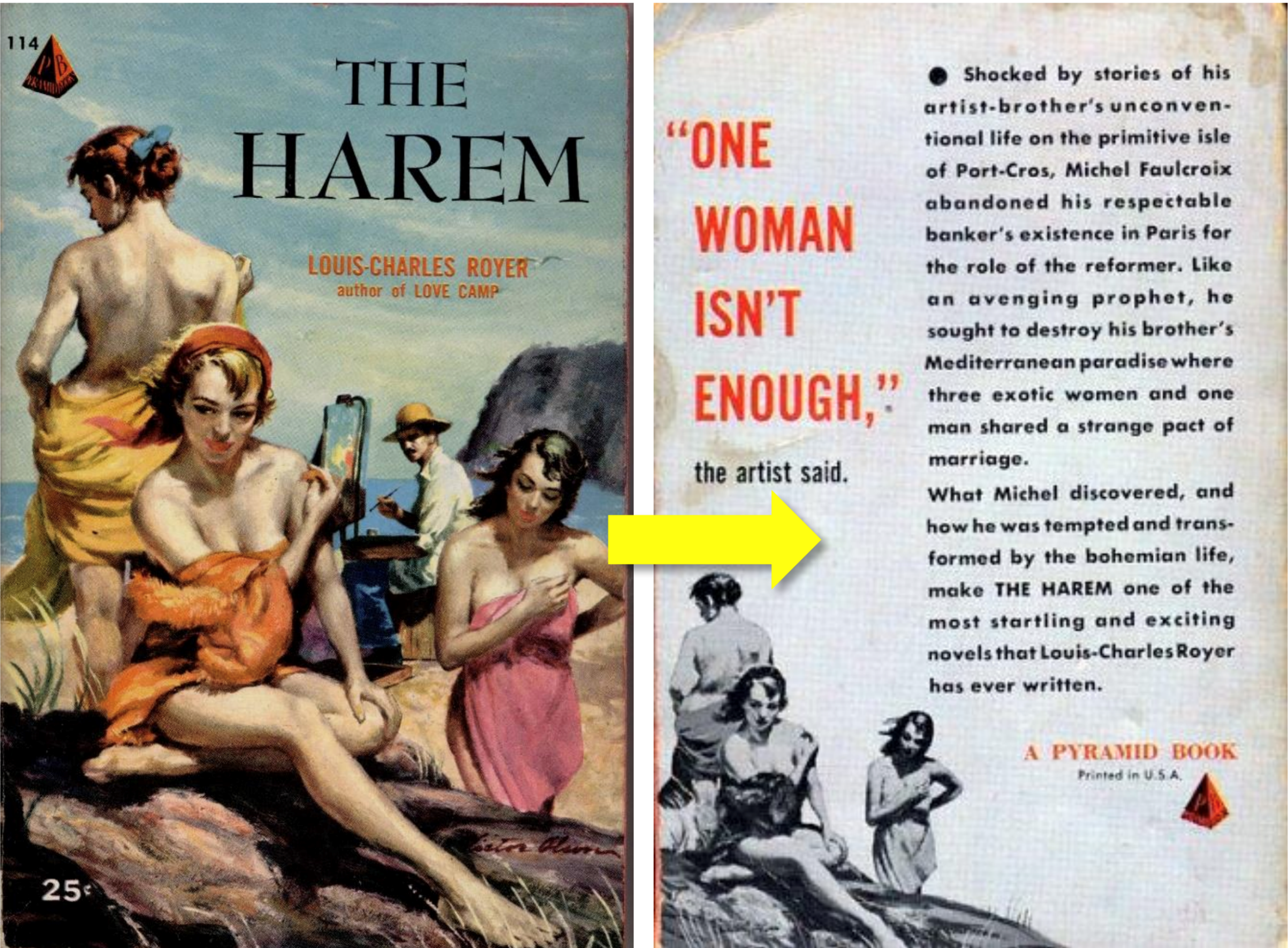

Figure 4. The Harem, Louis Charles Royer, 1954.

Figure 5. King of the Harem Heaven, Anthony Sterling,1960.

Figure 6. Hazel's Harem, Don Holliday, 1965.

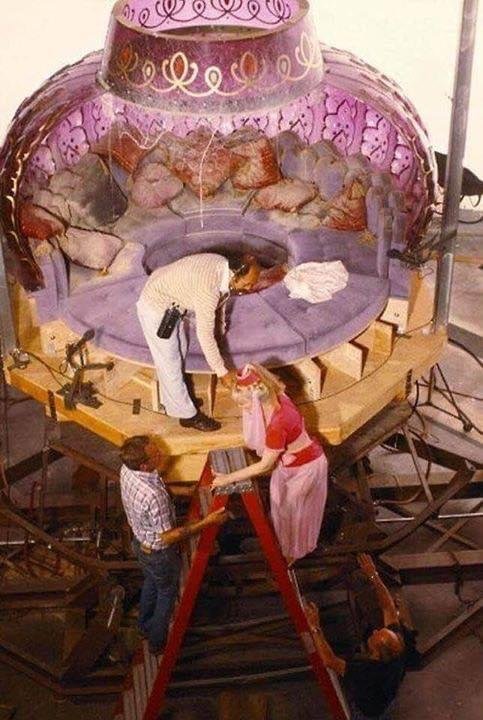

Figure 7. Barbara Eden (as Jeannie) climbs into her Genie bottle. The oculus, lavender color palette, red accents, and blonde hair eerily connect to Hazel and her bedroom.

The Harem: Conflicting Depictions in Modern Eastern Memoir and Mid–Twentieth-Century Western Pulp Fiction

Lee Casson, Johns Hopkins University

Writing about multifactorial religious, political, and sexual underpinnings of Middle-Eastern culture, three influential scholars—Azar Nafisi from Iran, Lelia Ahmed from Egypt, and Joumana Haddad from Lebanon—challenge Westerners’ estimations of womanhood within these geographic boundaries. Even more so, each writer often situates her autobiography within a harem, a private domestic space reserved only for women: around a reading group in Tehran (Nafisi), within a lush urban retreat outside of Cairo (Ahmed), and inside an adolescent’s bedroom in Beirut (Haddad). The term harem, however, holds pejorative connotations—which frequently revolve around Westerners’ prurient, homoerotic assumptions about lonesome, cloistered women devoid of men (see, for example, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s The Turkish Bath, circa 1860 [Figure 1])—yet Ahmed provides a thoughtful denotative rebuttal: “[Harem] can also be defined…as a system whereby the female relatives of a man—wives, sisters, mother, aunts, daughters—share much of their time and their living space, and further, which enables women to have frequent and easy access to other women in their community, vertically, across class lines, as well as horizontally.”[1] This considerate definition, in fact, applies to the harems that readers visualize within these scholars’ stories: Nafisi’s students dissect Western literature to comprehend Islamic fundamentalism through narrative allegory[2]; Ahmed’s female relatives learn that “through religion…one pondered the things that happened, why they had happened, and what one should make of them”[3]; and Haddad’s refuge—her bedroom, a place of relative safety apart from her “parents’ [Christian] conservatism” and from her “all-girls religious school”—stimulates her (sexual) maturation through “the world of books and writing.”[4] Moreover, the documentary The Secrets of the Harem underscores this socio-reality of the harem: “We should think of [it] as a unique place—as a collection of females who were more highly educated and more highly trained in a variety of ways than were women in the general society.”[5]

The Harem and Western Art

Nevertheless, Western artistic hegemony (alongside imperialism and xenophobia) conscripts for its citizens a cruelly sexualized harem: a lurid Oriental bordello for the polyamorous patriarch; a veritable Xanadu rife with requisite nudity, intoxicating aphrodisiacs, and insatiable concubines. Jean Léon Gérôme, a French Orientalist, for example, established this very image in The Large Pool of Bursa during the 1800s (see Figure 2)—at a time of escalating European colonization of the Middle East. In the painting, Gérôme carefully positions the tropes of Oriental harems: languid odalisques (plentiful, of course); abundant hookahs (with opium, probably); a barbaric man (propositioning a member of the collective, ostensibly); and trafficked peoples (from Africa, likely suggesting even more pornographic possibilities for the sadomasochistic fantasist). In the groundbreaking book Orientalism, Edward Said discusses artists like Gérôme, who fabricated “accounts of exotic adventure…[by appropriating] specific places, peoples, and civilizations”: “Orient idioms became frequent…and…took hold in European discourse…[so that] every European, in what he could say about the Orient, was consequently a racist, an imperialist, and almost totally ethnocentric.”[6]

This malicious stereotype dominated Western art, especially from France, during the nineteenth century (e.g., Ali)[7]—and continued well into the twentieth century, soon infiltrating the imaginations of American illustrators. These kind of artists—who elucidate a product’s purpose through visual narration (i.e., the book jacket)—chiefly influenced the pulp-fiction genre (i.e., paperback potboilers) within mid–twentieth-century American literature, thrashing audiences with salacious scenes of dangerous characters: bloodthirsty murderers, extraterrestrial subjugators, wicked Native Americans, naughty housewives, devious children, reprehensible lesbians and gay men, and, yes,Orientalwomen, geographically identified via the novel’s sensational cover—a confluence of coded text and an alarming image. Ed Hulse, inThe Art of Pulp Fiction, concurs, explaining that “enterprising publisher[s recognized] the paperback cover’s true potential as a marketing tool.”[8]Further clarifying this point, Katherine Forrest inLesbian Pulp Fictionadds, “An inverse law seems to be at work on pulp fiction novels: the better and more honest the book, the more its jacket copy must moralize against it.”[9]Thus, this brief analysis turns toward artistic and literary quasi-mimesis: how Western, masculine preconceptions of the harem penetrate the illustrations and comments on three pulp-fiction novels:The Harem(two editions),King of the Harem Heaven, andHazel’s Harem.

Louis Charles Royer’s The Harem

A popular writer of erotic French fiction, Louis Charles Royer (1885–1970) wrote Le Sérail (translation: seraglio, a term for the women’s apartment in an Ottoman palace) in the early 1930s. To advertise the salacious content of the novel—a melodramatic yarn about polyamorous relationships between a painter, his models, and his brother—Royer’s publishing house (presumably the firm Roman) turned to noted illustrator Jean-Gabriel Domergue (1889–1962), a cousin of Henri de Toulouse Lautrec. Domergue’s illustration (see Figure 3) reveals a combination of oriental and occidental ciphers: A French model—her Western features exaggerated, her post-coital gaze implied—poses seductively before a mashrabiya, a dividing screen used within many Middle-Eastern homes. Upon receiving these codes, the literary consumer understands the terms of the narrative bargain: Once situated within a mock-Eastern locale—in this case, an ersatz harem/seraglio within the Mediterranean Sea (or rather: not France)—European sophisticates lose their Western inhibitions, shedding their morals—and their clothes.

English Translation of Louis Charles Royer’s The Harem (1954)

Gaining popularity, Le Sérail promptly caught the attention of the editors at Pyramid Books, an American publishing firm that translated the novel to English in 1954. Commissioned to create a new illustration, Victor Olson (1924–2007), a prolific American artist, whose work hangs in the Smithsonian Institute, pushed the bounds of propriety even further, delivering a canvas (which recently sold for $4,000.00 at auction) that became even more sexualized: A painter surveys his models—nay, his harem—whose sartorial seduction mesmerizes eager consumers of literary erotica. Here, even mere suggestions of Middle-Eastern womanhood—a harem, silky togas, a desert-like locale (i.e., a sandy beach)—prey upon Western expectations of sexual lawlessness within the Mediterranean and Aegean Seas, intercontinental waterways that adjoin Europe and Anatolia, a crossroads of Christianity and Islam. The illustration—once adjoined to the novel’s summary on the back of the book (see Figure 4)—spins further the carnal course of the plot: “Michael Faulcroix abandoned his respectable banker’s existence in Paris for the role of the reformer. Like an evening prophet [a coded word, I argue], he sought to destroy his brother’s Mediterranean paradise where three exotic women and one man shared a strange pact of marriage.” As did Gérôme earlier, Royer, Domergue, and Olson (alongside their publishing houses) cruelly appropriate the harem, converting its familial function to pornographic playground—and prison.

Anthony Sterling’s King of the Harem Heaven

Published in 1960, Anthony Sterling’s King of the Harem Heaven continues the saga of the American pulp-fiction novel. The story—a sensationalized account of the House of David, a religious cult, whose leader, Benjamin Franklin Purnell, demanded celibacy from male members yet pursued sexual relationships with female members, including teenagers[10]—relies on familiar Orientalist tropes for savvy marketing purposes (see Figure 5): a commanding sheik, a naked concubine, a billowy thawb, the Quran, explicit carnality, palm trees indicative of Mediterranean and Mesopotamian fertility, and an island—now situated within Lake Michigan, a setting that presumably implies (again) an anti-democratic, anti-Western protectorate. Moreover, the back of the book reveals a linguistic trove of semantic delights:

Some people said he was mad, some believed he was a Holy Man—but many knew he was a black-hearted opportunist and a religious charlatan the like of which the world had never seen. This was a man who created and reigned over an absolute monarchy (within the greatest democracy in the world), now threatening his slaves with death, now promising eternal salvation, now banishing to a lonely island those who refused to bend to his will. This was Ben Purnell, King of the House of David—libertine, ravisher of teenage virgins, and conman supreme—who parlayed a self-appointed Messiah-hood into a ten-million-dollar empire and lived on a lavish scale unrivaled by anything out of The Arabian Nights.[11]

The book’s shocking blurb (just like the illustration) employs vulgar tropes aplenty, exploiting both vocabulary and connotation to guide the American consumer’s initial interpretation of the story (and subsequent purchase). Grounded in doublespeak, certain words (e.g., “religious charlatan,” “absolute monarchy,” “slaves,” “teenage virgins,” “Messiah-hood,” and “The Arabian Nights”—together conjure Oriental harems, turning these sanctified spaces into bagnios and Turkish baths—or more forcefully put: into maritime whorehouses independent of Western dominion.

Don Holliday’s Hazel’s Harem

By the mid-1960s, the literary world found itself in the midst of a progressive boon: Politically, the democratic policies of Presidents Kennedy and Johnson displaced the conservative directives of President Eisenhower and Senator McCarthy; socially, the Western world, especially America, experienced the profound implications of second-wave feminism, the Civil Rights movement, the Vietnam War, LGBTQ+ visibility, Woodstock, and other culturally significant milestones; and artistically, erotica finally became legal—at least, if it were mailed via the United States Post Office (in large part owing to the arguments of Allen Ginsburg, who successfully fought obscenity charges against his collection of poems, Howl). As a result, pulp fiction became increasingly, well, more pornographic; publishing houses released hundreds upon hundreds of sexually-aggressive novels with titles like Stud Prowl (1963),Any Bed for Myra (1965), Brothers in Love (1967), and Hazel’s Harem (1965)—all four of which were written by Don Holliday, a ubiquitous pseudonym used for countless stories of the pulp-fiction genre. Research bares that Don Holliday, for instance, could have been (1) Victor J. Banis, a noted author of queered literature during the 1960s, (2) Lawrence Block, an award-winning novelist of mysteries, or (3) Hal Dresner, a multi-talented writer, responsible for teleplays (M*A*S*H), screenplays (Catch-22), and numerous short stories; however, mere speculation governs any final explanation about the pseudonym’s actual identity. Moreover, the cover of Hazel’s Harem (see Figure 6) exposes the same Orientalist concerns: Western hegemony, ethnocentric appropriation, and fetishization and subjugation of women. Aside from flashing a cautionary advertisement—“Shame was the name for Hazel’s Harem”—the illustration displays similar tropes: First, an imprisoned woman resides either within her Genie bottle—one part boudoir, one part penitentiary (after all, the sitcom I Dream of Jeannie aired its first episode in 1965; see Figure 7)—or within her panic room, safely hidden from naïve visitors (or the police). Secondly, a coded message appears for the shopper of adult literature: that a harem signifies both a bedroom—even a feminine one, replete with lavender tones and brass accents (despite its punitive insinuation of sexual malice)—and a brothel, where scores of women languish in an orgiastic hiatus, eagerly awaiting a virile man, who—quite literally!—will blow the lid off.

Concluding Thoughts

In the introduction to Pulp Friction: Uncovering the Golden Age of Gay Male Pulps (and there were many), Michael Bronski writes:

With their fabulously garish colors, their cartoonish, mock-heroic studs, and tempting titles…[the pulps] are old-time…iconography for a new, younger generation…. Falling somewhere between kitsch and kitchen decorations, these images, no longer on book jackets, now grace refrigerator magnets, postcards, and address books. Often they straddle clear-cut categories: they can be both hot and humorous, nostalgic and trendy, historic and emblematic of a contemporary sensibility. They are artifacts from the past that have acquired new, ironic meanings [for today’s audiences].[12]

Although Bronski’s comments have been edited—the wordsgayandhomosexualhave been removed (clearly, not due to censorship)—they still speak to the enormity of the pulp-fiction genre: how these books salaciously typecast marginalized communities (e.g., gay men, women, Middle Easterners) for a hetero-normative, White, Christian readership during the mid-twentieth century. In a similar manner, Edward Said situates his criticism (of pulp fiction, broadly speaking) within the racist, ethnocentric, xenophobic confines of Orientalism—how “[Western] readers of [Oriental] novels…converg[ed] upon such essential aspects of [the Middle East]…as…Oriental sensuality, and the like.”[13]Both Bronski and Said reveal the blatant sexualization inherent within Orientalism, and in the previous examples—Royer’sThe Harem, Anthony Sterling’sKing of the Harem Heaven, and Don Holliday’sHazel’s Harem—an appropriated image of the harem becomes perverted through Western conscription and hegemony. Indeed, these three books hold negligible literary value—yet they become an important component of the Oriental historiography, explaining to scholars the immensity of spiteful, sensational stereotypes surrounding Middle Easterners.

Notes

1 Leila Ahmed, “Western Ethnocentrism and Perceptions of the Harem.” Feminist Studies 8, no. 3 (1982): p. 524.

2 Azar Nafisi, Reading Lolita in Tehran (New York: Random House, 2003).

3 Leila Ahmed, A Border Passage: From Cairo to America – A Woman’s Journey (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1999), 121.

4 Joumana Haddad, I Killed Scheherazade: Confessions of an Angry Arab Woman (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2011), 36-37.

5 The Secrets of the Harem: Islam’s Palace of Pleasure. Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IoPDXofThHs.

6 Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books, 1979), 203-204.

7 Isra Ali, “The Harem Fantasy in Nineteenth-Century Orientalist Paintings,” Dialectical Anthropology 39, no. 1 (2015): pp. 33–46.

8 Ed Hulse, The Art of Pulp Fiction: An Illustrated History of Vintage Paperbacks (San Diego: Elephant Book Company, 2021), 28.

9 Katherine Forrest, Lesbian Pulp Fiction: The Sexually Intrepid World of Lesbian Paperback Novels 1950-1965 (San Francisco: Cleis Press, 2005), xvi.

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_of_David_(commune).

[11] To see an image of the back cover, visit https://www.worthpoint. com/worthopedia/house-david-book-king-harem-heaven-1738724781.

12 Michael Bronski, Pulp Friction: Uncovering the Golden Age of Gay Male Pulps (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2003), 1.

13 Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books, 1979), 203.

Copyright © 2023 by Association of Graduate Liberal Studies Programs