Catherine Behan graduated in May with a Master’s of Arts in Liberal Studies with the honor of the Excellence in Graduate Liberal Studies Award from Indiana University South Bend. She earned her undergraduate degree in journalism from the University of Kansas and had a career helping university professors garner attention for their academic research before embarking on her own research into the poor educational outcomes of maltreated children. She is currently an associate professor of English and French at IU South Bend. Catherine lives with her husband and a rambunctious puppy in South Bend while she continues her research.

excellence in interdisciplinary writing

Graduating from High School: The “Elixir” for Public Health

Catherine Behan, Indiana University South Bend

Education is a fundamental way to increase health and well-being.[1] In addition, the more education students receive, the lower their mortality rate.[2] Yet the percentage of students in the United States who graduate from high school four years after they begin grade nine has been below 90.7%—the goal of Healthy People 2030[3]—for its entire history. Graduation rates vary from state to state and among certain populations. de Brey et al.[4] noted that in 2016, 33% of Hispanic adults age 25 and over had not completed high school, compared with 8% of White adults, 10% of Black adults, and 17% of American Indian/Alaska Native adults. The Healthy People 2030 website cites a goal of increasing the baseline rate of public-school students graduating in four years from 84.1% (in 2015) to 90.7% by 2030. It is a goal that could be quite challenging without widespread understanding of the depth of the problem and focused attention and intervention.

Without that understanding and intervention, however, stagnant graduation rates harm not just individuals but also the economy overall. A 2015 study by the Alliance for Excellent Education estimated that increasing the high school graduation rate to 90% nationally would create more than 65,000 new jobs, increase gross domestic product by more than $11 billion each year, increase annual earnings by more than $7 billion, and increase federal tax revenue by more than $1 billion each year.[5]

Although the importance of a high school education for personal well-being and economic health is clearer today, education beyond elementary school only became common about 100 years ago. High school attendance and graduation were relatively rare in America before the 1900s, then exploded, particularly in the Northern states from 1910 to 1940.[6] Only about 8.3% of the children born between 1886 and 1890 had a high school diploma. In contrast, about 46% of those born between 1946 and 1950 had earned their degree. Between 1900 and 1970, the graduation rate increased from 6% to 80%, then stayed relatively steady through the rest of the century,[7] and has increased only slightly since then.

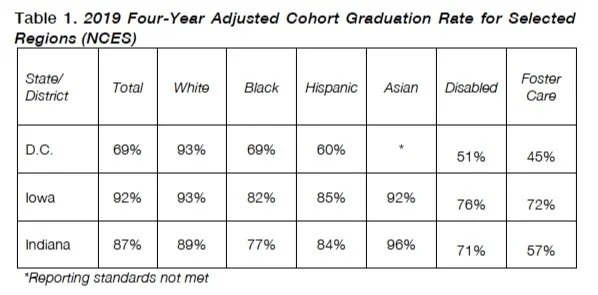

High school graduation rates among all students improved from an average across the country of 79% in the 2010–11 school year to an average of 86% in the school year ending in 2019.[8] However, states vary widely from a low in 2019 of 69% in the District of Columbia to a high of 92% in Iowa. About 87% of Indiana students graduated from high school in 2019. However, these overall graduation rates—even over time—paper over discrepancies in rates among disadvantaged groups that continue today. In the school year ending in 2019, 89% percent of White students graduated with their cohort, compared with 80% of Black students, 82% of Hispanic students, 74% of American Indian/Native Alaskan, and 80% of those categorized as economically disadvantaged, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.[9] Disabled children and children in foster care fare even less well. Looking at those same states or districts, we can see the outcome disparity in Table 1.

Poor health reduces children’s ability to learn,[10] and lower graduation rates contribute to lifelong health issues including cardiovascular disease and lower life expectancy.[11] Matthews et al.[12] found that those with lower education levels were more likely to have health problems signaling coronary disease and were more likely to smoke, have little exercise, and be angry, be depressed, and have little social support, among other results. They conclude that because advanced education increases protections against coronary disease, it is important to increase education levels.

As Freudenberg and Ruglis noted, poor health can also diminish educational attainment. Zbar et al.[13] found that those children who had had difficulty with internalizing problems as children, such as anxiety or psychosomatic problems (which are very common among children who have been maltreated and therefore be in foster care), were twice as likely to have lower educational attainment—less than a high school diploma—than their peers without these problems, similar to outcomes for children with externalizing problems, such as ADHD. Improving these mental health issues could increase educational attainment and mitigate inequalities in mental health, they advocate.

Freudenberg and Ruglis wrote an article for Preventing Chronic Disease, a peer-reviewed public health journal sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). They advocated ways that health professionals and educators could work together in research, advocacy, and intervention to improve health outcomes by improving rates of high school graduation. However, in the 13 years since, only one of their recommendations— advocating for programs like sex education that could reduce dropout rates—appears to have been implemented by federal agencies, in this case, CDC Division of Adolescent and School Health (DASH). One of their recommendations, which echoed a recommendation from 1993, was to have organizations in health care and education coordinate efforts to improve education, health, and well-being for children. That recommendation went nowhere.

Foster Children at Greatest Risk

As shown in Table 1, children who are in foster care because of a finding of maltreatment graduate at far lower rates than their peers, with an average national rate of about 54% for those reporting data.[14] The lowest was Colorado, with only 27% of foster children graduating with their peers. The highest was Montana, where 87% of foster children graduate from high school, about the same rate as their peers overall. Just 57% of foster youth in Indiana graduate with their peers. Those low graduation rates remain largely unchanged over the previous decades. Taylor[15] was among the first academic researchers to look beyond the health and safety of foster youth, explaining that “education occupies a central position; the consequences of not learning successfully are fateful for the child,” noting that about 50% of children in foster care then did not graduate from high school.[16] Since the early decades of federalized foster care in the 1970s, graduation rates for foster children haven’t budged and, in some cases, have declined. Despite the consistently low rates of graduation among children in foster care, little has been done to improve their educational attainment.

The low graduation rate is a major reason that children who have been mistreated have significantly lower levels of employment and earnings throughout their lives.[17] In addition, it may be difficult for the public to understand the risks maltreated children face because the public tends to look at it through a lens clouded by views of race and poverty. Much of the public conflates poverty and neglect—they’re more likely to see a parent as neglectful if they are poor or homeless and less likely to see and report it if the parents are wealthier or appear overwhelmed by, for example, a family illness.[18] However, Finkelhor et al.[19] found that there was no statistical difference in the children he surveyed who reported maltreatment in the previous year either by income or race. Child maltreatment is all around us, in all strata of society. To try to address the problem of low educational attainment by children in foster care, Congress passed the Every Child Succeeds Act (ESSA) in 2015.[20] In 2019, the U.S. Government Accountability Office conducted a study into why teachers and social workers weren’t collaborating effectively to help foster children achieve better educational outcomes as they were required to do under ESSA (GAO 19-616). Their findings—that there was too much turnover among social workers and that educators didn’t know enough about the status of children in their schools—received little attention or action. ESSA’s requirements that children in foster care have more stable housing, for example, to improve their educational cohesion has not created any policy change or additional research.[21]

ESSA’s policy guidance to ensure the housing and educational stability of children in foster care is backed up by scientific research. Increasing stable housing—that is, reducing the number of transitions from one foster family to another—can even ameliorate some of the original damage of the children’s initial maltreatment.[22] Neuroscientists reviewing fifty-nine studies of foster placement instability found significant effects on the development of the brain’s frontal cortex, the executive function of the brain. Poor executive function, they note, is associated with increasing risks of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), behavior disorders, and other psychopathologies. Some of the studies they reviewed also note that placement instability is predictable and preventable, and that stability could inhibit neurobiological and psychiatric issues of even past problems.

Social science research agrees that if the common issue for children in foster care who frequently move from one home to another—uprooting their lives and education repeatedly—was minimized, they tend to find success.[23] Yet again, at least 21% of children in foster care—who, by definition, have already experienced trauma from their initial maltreatment—continue to have at least more than one placement. Some report dozens of moves. So, we know what can help improve outcomes for these children, but we don’t implement policy or spend the money to facilitate those improvements.

In addition, the cost of child maltreatment to the economy is stunning but largely invisible: Peterson et al.[24] estimate that the per-victim lifetime costs of non-fatal child maltreatment is $830,928 because of increases in long-term healthcare, child welfare services, criminal justice, special education, and, importantly, loss of productivity. The lifetime economic cost to society of investigated (authors’ emphasis) annual incidences of child maltreatment is $2 trillion.[25] As a comparative, the 2020 federal relief package for the pandemic, the CARES Act, cost about $2 trillion.[26] Because child maltreatment is underreported, that $2 trillion is likely vastly higher.

Only since 2015 with the passage of ESSA have states been required to track graduation rates for children in foster care. Some states, however, still do not comply, either providing no data or data that do not meet reporting standards.

The dismal health and well-being outcomes of children who have been mistreated exemplify why Healthy People 2030 included increasing high school graduation rates as a key indicator to improving health. For this study, I explore specifically why educational outcomes are distinctly poor for children in the foster care system because their graduation rates are markedly lower than other groups and because improving the rates of those struggling the most could also improve educational attainment more broadly. Increasing graduation rates overall is possible because the reasons most students fail to graduate are similar to those students who had been maltreated: navigating home or school environments they find toxic, a need for connectedness to others, and being in foster care itself.[27]

Providing Equitable Access for All: A Social-Ecological Model

As demonstrated through a review of local high school campuses in one city, South Bend, Indiana, those schools with the highest graduation rates have modern, vibrant grounds and buildings, such as St. Joseph High School with a graduation rate of 96.5.[28] Those with the lowest graduation rates, such as Clay High School with a rate of 78.1%, are more difficult to walk to and around, have few places to gather and become more connected, and tend to be empty when school was not in session. Facilities help keep students connected to school and be part of its community, which increases rates of graduation.[29] Clay High school has disheveled athletic fields and a parking lot larger than green space for children to mingle and relax.

However, improving graduation rates requires broader solutions we can see more clearly through a Socio-Ecological Model from individual factors to society as a whole.

Individual

Individual characteristics including poverty, foster care status, race, disability, and poor health itself reduce children’s ability to learn.[30] In addition, lower graduation rates contribute to lifelong health issues, including cardiovascular disease and lower life expectancy.[31] Research from England also shows that one of the two strongest variables for risks that mothers will abuse their children is education level[32] (younger parents and those with less than a high school equivalent degree were more likely to abuse their children). Therefore, increasing educational outcomes for those who may become parents can both help prevent child maltreatment and increase the educational attainment of children themselves, therefore lowering future child maltreatment and poor health outcomes later in life.

Possible interventions:

• Increase or make permanent child tax credits and support to reduce poverty.

• Create programs to support families to prevent child maltreatment in the first place and support families and children to overall health and well-being once maltreatment has occurred—regardless of their current legal status of being in the child welfare system. The costs of these supports could be recouped by adults who had been maltreated earning higher incomes and needing less treatment for poor mental and physical health outcomes.

• Provide individual support and counseling to students who are struggling—personally or academically or both.

Resolving individual characteristics is a lower level of influence and would require important community and policy changes that I will discuss below.

Relationships

Children’s relationships with both their peers and adults are an important level of influence in educational achievement.[33] Children who have more support from adults including parental figures, teachers, and others in the community have better educational outcomes and emotional well-being.[34] Guo et al use the Social Ecological Model as a framework to understand how social supports impact psychological well-being. Increased family income improves psychological well-being. In addition, students with strong support of other students helped improve the well-being of not just wealthier children but boost well-being for all children.

Ahrens et al.[35] also found that for children in foster care, mentoring relationships with non-parental adults were important to improving educational attainment and other positive outcomes, but many barriers stand in the way of forming those relationships, including instability of placements. They recommend increasing programs to facilitate these relationships for children in care. In addition, Neal[36] showed that adult supporters enabled foster children to increase their education beyond high school by providing guidance, emotional caring, and increased stability. In my interviews with former foster children, every student who went to college volunteered that they would have been better off if they had relationships like these and would be more successful once in higher education if they had mentoring relationships with adults—particularly those who had had experiences as foster children themselves.

Blakeslee and Best[37] found that interpersonal difficulties, such as challenging relationships with caregivers and biological family members, as well as difficulty making friends, could stand in the way of building a network of support. However, when children feel part of a team and have a voice in their lives, they found increased support. In addition, Meng et al.[38] found that children who had been maltreated had better outcomes with protective characteristics such as resilience as individuals, as well as those with stronger social engagement.

Possible interventions:

• Increase programs to facilitate supportive adult relationships for children, particularly those in foster care.

• Reduce frequent home changes for children in care to strengthen relationships, stability, and increase resilience.

Communities and Organizations

Education is a community environmental issue and, in addition to the physical environment, communities and organizations can have a high level of influence in improving educational achievement. However, this might require significant changes to improve outcomes, as demonstrated by little community input or understanding of the results of South Bend Community School Corporation’s successful 2020 referendum for higher tax rates to improve schools. South Bend’s lower-performing high schools had lower quality of recreation facilities, dilapidated housing nearby, and little walkability. They also have far fewer congregation places that can increase connectivity to their peers and the institution itself.

For children in foster care, Johnson et al.[39] found that educational instability owing to changes in placements reduced a sense of belonging in school, which reduced their educational outcomes. As Clemens et al.[40] described, educational stability in high school could be an important key in closing the educational attainment gap between foster children and their peers.

In addition, the healthcare system may be a barrier to improvements in educational outcomes, particularly for children in foster care. Because children who have been maltreated are more likely to have health issues—physical, mental, and dental—from the trauma of abuse and neglect, Szilagyi et al.[41] found that pediatricians have a critical role in ensuring that these children get appropriate care. One of many challenges, however, results from foster children having frequent changes in placements, they note. A key issue for pediatricians is not just trauma-informed and compassionate care but also care coordination and advocacy.

Children in foster care are eligible for Medicaid, but the number of health providers who accept Medicaid patients is low.[42] This is particularly problematic because of both increased health issues and placement instability, which can make it difficult to maintain continuity of care. If the healthcare system were to advocate for children and be aware of the potential for child abuse and neglect, these children could have a better chance for increased educational attainment through appropriate treatment.

For general education support of all students, there appear to be a few organizations in South Bend focused on helping certain groups of students to increase their success in school through services such as leadership training and tutoring. Examples include Transformation Ministries, the South Bend Empowerment Zone, and La Casa de Amistad. However, it does not appear that there are many programs to assist children in foster care to ensure stability in school and home and other ways to improve educational outcomes except for the overstretched Department of Child Services (DCS) and volunteer Court Appointed Special Advocates (CASA). DCS social workers supervise child placements and outcomes but have a heavy caseload and significant turnover. In addition, their focus is on placement safety rather than educational achievement. CASA is staffed primarily by volunteers who do work with schools in addition to other organizations to advocate for the best interests of the children in their charge. However, educational achievement is not their focus either. Nonetheless, research shows that simply having a CASA volunteer improves educational outcomes for children in foster care by building relationships with adults and increasing stability.[43]

In addition, there is little understanding of or concern for children in foster care, in part because research shows that most people think child maltreatment happens in families that aren’t like their own.[44]

Potential interventions:

• Educate those in the healthcare system about the importance of education as well as the influence of trauma on long-term wellness.

• Increase funding to enable more children in foster care to have a CASA assigned to their case.

• Create a coalition of organizations to drive support for children’s education as a whole and create a task force to produce educational and community support for children in foster care in particular.

• Improve public understanding of the costs for poor educational outcomes to the community as a whole to drive support for these programs.

Policy and Society

Every year, about 16% of children nationally do not graduate high school on time, leading to lower incomes and health concerns. However, our national education policy focuses not on children achieving an education but in achieving standardization and test scores. In addition, about 40% of all children face mistreatment in their lifetimes and only about 50% of children who are in foster care because of mistreatment graduate on time. Changes in national and state policy—as well as societal concern about educational attainment—constitute a significant level of influence in closing the achievement gap.

Few people understand the breadth and depth of the problems created by child maltreatment, and very little is done to address poor outcomes, even when federal law requires it. For example, when Congress passed ESSA in 2015, it required that educators and child welfare workers coordinate to improve children’s educational outcomes and to minimize moves to other foster homes. In the six years since, those legal requirements have still not been met. At the same time, perhaps not coincidentally, in some states, including Indiana, the rate of foster children graduating from high school has declined. Most importantly, there is extremely little public knowledge or education to understand the problems these children face or how we can mitigate them.

Education about educational outcomes and how they impact long-term health may be one of the biggest gaps not just in South Bend but also nationally. South Bend, however, exemplifies the long-term struggle to rectify educational inequities, notably in rates of school disciplinary actions.[45] If the local news is the prime method that people learn about education, residents might also get a skewed portrait because of the positive coverage of private and high-performing schools such as St. Joseph and nearby Penn-Madison High School and negative coverage of lower-performing school, such as a recent example, a fight at Clay High School. There is even less opportunity to learn about the education of children in foster care. Only since 2018 are states required to track the graduation rates of children in foster care. However, the only news coverage of graduation rates at all has been to compare the rates between high schools.[46] News stories do not educate people about the reasons for the discrepancies or about the varying outcomes for subgroups of students, such as those who are economically disadvantaged, are Black or Hispanic, or are in foster care—although those data are publicly available.[47]

This lack of public information can enable child maltreatment to continue because a primary reason that child maltreatment occurs unabated is a concern about intruding on family privacy, which leaves abuse hidden,[48] as well as the belief that abuse happens in other people’s families. A significant improvement could be made with additional education.

To improve outcomes for children in foster care, including education outcomes, Font and Gershoff[49] recommend improving staffing levels and funding in the foster care system. Other recommendations include professionalizing the workforce, increasing retention of quality foster homes, increasing system transparency and accountability including citizen review panels, carefully studying the relationship between the system and outcomes, and tracking not only safety but also well-being.

Finally, there is little research into interventions to improve high school graduation rates in general and specifically for foster children.

Possible interventions:

• Create a coalition of organizations to provide massive outreach across the nation to educate people—including educators and healthcare workers—about the problem and ways to solve it. This campaign should also highlight the costs to society over the long-term.

• Increase research into interventions to improve high school graduation rates.

• Conduct research into state programs such as those in Wisconsin and Washington to understand how those programs improved (or not) outcomes for children in care.

• Change policy to ensure that requirements under laws such as ESSA are enforced so that maltreated children are more likely to have stable homes.

• Increase funding for education to reduce inequities and build programs to support students.

Conclusion

We have good information—although we need more—to improve the educational achievement and improve health and well-being for all children by providing the support students need to graduate from high school and be prepared for more education if they choose. Improving those outcomes would also improve society as a whole by increasing health (and reducing costs for health care) as well as improving economic benefits for individuals and the economy. Improving educational outcomes would also reduce child maltreatment itself, thereby improving the future potential of nearly one-third of children in the United States.

However, we have too little broad understanding of just how many children fail to graduate from high school, generation after generation. This fact breeds little concern and widespread complacency. Together we can take action to improve lives by meeting or exceeding the Healthy People 2030 goal of 90.7% of students graduating from high school.

Notes

[1] Nicholas Freudenberg and Jessica Ruglis, “Reframing School Dropout as a Public Health Issue,” Preventing Chronic Disease 4, no. 4 (2007): A107.

[2] Michael T. Molla, Jennifer H. Madans, and Diane K. Wagener, “Differentials in Adult Mortality and Activity Limitation by Years of Education in the United States at the End of the 1990s,” Population and Development Review 30, no. 4 (2004): 625–46.

[3] https://health.gov/healthypeople.

[4] Cristobal de Brey, Lauren Musu, Joel McFarland, Sidney Wilkinson-Flicker, Melissa Diliberti, Anlan Zhang, Claire Branstetter, and Xiaolei Wang, Status and Trends in the Education of Racial and Ethnic Groups 2018, (Washington, DC: NCES, IES, U.S. Department of Education, 2019), 228.

[5] “Increasing National High School Graduation Rate Key to Job Creation and Economic Growth, New Alliance Analysis Finds | All4Ed” (December 15, 2015). https://all4ed.org/press_release/increasing-national-high-school-graduation-rate-key-to-job-creation-and-economic-growth-new-alliance-analysis-finds/.

[6] Claudia Goldin, “America’s Graduation from High School: The Evolution and Spread of Secondary Schooling in the Twentieth Century,” Journal of Economic History 58, no. 2 (1998): 345–374.

[7] Richard J. Murnane, “U.S. High School Graduation Rates: Patterns and Explanations,” Journal of Economic Literature 51, no. 2 (2013): 370–422.

[8] https://nces.ed.gov/.

[9] https://nces.ed.gov/.

[10] Freudenberg and Ruglis.

[11] Karen A. Matthews, Sheryl F. Kelsey, Elaine N. Meilahn, Lewis H. Muller, and Rena R. Wing, “Educational Attainment and Behavioral and Biologic Risk Factors for Coronary Heart Disease in Middle-Aged Women,” American Journal of Epidemiology 129, no. 6 (1989): 1132–1144. See also, Molla et al., 2014.

[12] Matthews et al.

[13] Ariella Zbar, Pamela J. Surkan, Eric Fombonne, and Maria Melchior, “Early Emotional and Behavioral Difficulties and Adult Educational Attainment: An 18-Year Follow-up of the TEMPO Study,” European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 25, no. 10 (2016): 1141.

[14] https://nces.ed.gov/.

[15] Joseph L. Taylor, “Remedial Education of Children in Foster Care,” Child Welfare 52, no. 2 (1973): 123–128.

[16] Ibid., 124.

[17] Janet Currie and Cathy Spatz Widom, “Long-Term Consequences of Child Abuse and Neglect on Adult Economic Well-Being,” Child Maltreatment15, no. 2 (2010): 111–120.

[18] Sasha Emma Williams, “Redrawing the Line: An Exploration of How Lay People Construct Child Neglect.” Child Abuse & Neglect 68, (June 2017): 11–24.

[19] David Finkelhor, Richard Ormrod, Heather Turner, and Sherry L. Hamby, “The Victimization of Children and Youth: A Comprehensive, National Survey,” Child Maltreatment 10, no. 1 (2005): 5–25.

[20] Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration. 2015. “Public Law 114 - 95 - Every Student Succeeds Act.” Government. Govinfo.Gov. U.S. Government Publishing Office. December 10, 2015. https://www.congress.gov/114/plaws/publ95/ PLAW-114publ95.htm.

[21] Jaqueline M. Nowicki, personal communication, October 29, 2021.

[22] Phillip A. Fisher, Anne M. Mannering, Amanda Van Scoyoc, and Alice M. Graham, “A Translational Neuroscience Perspective on the Importance of Reducing Placement Instability among Foster Children” Child Welfare 92, no. 5 (2013): 9–36.

[23] Elysia V. Clemens, Trent L. Lalonde, and Alison Phillips Sheesley, “The Relationship between School Mobility and Students in Foster Care Earning a High School Credential,” Children and Youth Services Review 68 (September 2016): 193–201.

[24] Cora Peterson, Curtis Florence, and Joanne Klevens, “The Economic Burden of Child Maltreatment in the United States, 2015,” Child Abuse & Neglect86 (December 2018): 178–83.

[25] Peterson et al.

[26] Kelsey Snell, “What’s Inside the Senate’s $2 Trillion Coronavirus Aid Package.” NPR.org. March 26, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/03/26/ 821457551/whats-inside-the-senate-s-2-trillion-coronavirus-aid-package.

[27] America’s Promise, “Don’t Call Them Dropouts.” Accessed October 9, 2021. https://www.americaspromise.org/report/dont-call-them-dropouts.

[28] National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Home Page, Part of the U.S. Department of Education.” National Center for Education Statistics. Accessed October 18, 2021. https://nces.ed.gov/.

[29] Danita Henry Stapleton and Roy K. Chen, “Better Outcomes for Children in Treatment Foster Care through Improved Stakeholder Training and Increased Parent-School Collaboration,” Children and Youth Services Review 114 (July 2010): 105010.

[30] Freudenberg and Ruglis.

[31] Matthews et al.; Molla et al.

[32] Peter Sidebotham and Jean Golding, “Child Maltreatment in the ‘Children of the Nineties’ A Longitudinal Study of Parental Risk Factors.” Child Abuse & Neglect 24, no. 8 (2001): 1177–1200.

[33] America’s Promise.

[34] Yuqi Guo, Laura M. Hopson, and Fan Yang, “Socio-Ecological Factors Associated with Adolescents’ Psychological Well-Being: A Multilevel Analysis,” International Journal of School Social Work 3, no. 1 (2018).

[35] Kym R. Ahrens, David Lane DuBois, Michelle Garrison, Renee Spencer, Laura P. Richardson, and Paula Lozano, “Qualitative Exploration of Relationships with Important Non-Parental Adults in the Lives of Youth in Foster Care,” Children and Youth Services Review 33, no. 6 (2011): 1012–1023.

[36] Darlene Neal, “Academic Resilience and Caring Adults: The Experiences of Former Foster Youth,” Children and Youth Services Review 79 (August 2017): 242–248.

[37] Jennifer E. Blakeslee and Jared I. Best, “Understanding Support Network Capacity during the Transition from Foster Care: Youth-Identified Barriers, Facilitators, and Enhancement Strategies,” Children and Youth Services Review 96 (January 2019): 220–230.

[38] Xiangfei Meng, Marie-Josee Fleury, Yu-Tao Xiang, Muzi Li, and Carl D’Arcy, “Resilience and Protective Factors among People with a History of Child Maltreatment: A Systematic Review,” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 53, no. 5 (2018): 453–475.

[39] Royel M. Johnson, Terrell L. Strayhorn, and Bridget Parler, “‘I Just Want to Be a Regular Kid:’ A Qualitative Study of Sense of Belonging among High School Youth in Foster Care,” Children and Youth Services Review 111 (April 2020): 104832.

[40] Clemens et al.

[41] M. A. Szilagyi, D. S. Rosen, D. Rubin, S. Zlotnik, and the Council on Foster Care, Adoption, and Kinship Care, the Committee on Adolescence, and the Council on Early Childhood, “Health Care Issues for Children and Adolescents in Foster Care and Kinship Care,” Pediatrics 136, no. 4 (2015): e1142–e1166.

[42] Sarah A. Font and Elizabeth T. Gershoff, “Foster Care: How We Can, and Should, Do More for Maltreated Children,” Social Policy Report 33, no. 3 (2020): 1–40.

[43] Hersh C. Waxman, W. Robert Houston, Susan M. Profilet, and Betsi Sanchez, “The Long-Term Effects of the Houston Child Advocates, Inc., Program on Children and Family Outcomes,” Child Welfare 88, no. 6 (2009): 23–46.

[44] Price et al.

[45] “Indiana’s 2018 Graduation Rate Shows Slight Increase,” South Bend Tribune (South Bend, Indiana), January 2, 2019. https://www. southbendtribune.com/story/news/education/2021/09/03/indianas-2018-graduation-rate-shows-slight-increase/45934487/.

[46] Ibid.

[47] https://inview.doe.in.gov/.

[48] Lela B. Costin, Howard Jacob Karger, and David Stoesz, The Politics of Child Abuse in America (Oxford University Press, 1997).

[49] Sarah A. Font and Elizabeth T. Gershoff, “Reorienting the Foster Care System Toward Children’s Best Interests,” in Foster Care and Best Interests of the Child (Cham, Springer, 2020), 23–34.

Copyright © 2022 by Association of Graduate Liberal Studies Programs